Why Do Some Historians Believe Byzantine Art Included Government Propaganda

By Dr. Patrick N. Chase

Lecturer in Archæology

Stanford University

Power on earth was in one case – and sometimes even now – perceived as a result of power in heaven. The cracking double mosaic of Justinian and Theodora at San Vitale in Ravenna is a forceful exercise in demonstrating ability through art as propaganda, fusing political and religious imagery for a double argument of dominance. In the 6th century, many intellectual Christians, non necessarily an oxymoron despite the possibility thereof, would have found these mosaics hubristic. Even the contemptuous could accept found these mosaics troubling. Notwithstanding in that location are at to the lowest degree iii possible reasons why this propaganda was justifiable for a Byzantine ruler. The mosaics here are perhaps the greatest of early Byzantine if not all post-Roman mosaics; they do serve as embellishment to reinforce the grandeur of Justinian, perhaps simultaneously last Roman emperor and get-go Byzantine emperor.

But first, it is necessary to argue that this double procession is Byzantine and non either Roman or Palaeo-Christian. Although Justinian is often considered the last truly Roman ruler in the East and this art is in the Westward far outside of Constantinople as well as chronologically outside what is easily Byzantine a few centuries later, it is nonetheless Byzantine. No less than David Talbot Rice places Justinian and his world inside a new Byzantine framework "But more vital for fine art…was the reign of Justinian…for then the new Byzantine Empire was set on a sure foundation and an art and architecture which were both wholly Christian and as well wholly new." (1) This is also acceptable if i besides agrees with the thesis of John Julius Norwich that the dominion of Justinian (and Theodora) helped create a political temper that would prevail for centuries in Byzantium: "More than than whatever other monarch in the history of Byzantium, he [Justinian] stamped the Empire with his own character; centuries were to pass before it emerged form his shadow." (2)." It is these premises followed here. The authority of the emperor to convene Ecumenical Councils of the Church (553 CE) and finer hold the western Pope Vigilius between 545-553 mostly hostage against his will in or effectually Constantinople (although Rome was in hostile Goth hands anyway) are merely two evidences of this fusion of political and religious ability.

Justifications for the propagandizing elements in these mosaics are not difficult, peculiarly if i is Christian emperor, however that word Christian was understood at the fourth dimension given arable heresies and a politically-charged orthodoxy that often depended on more subtle factors similar a ruler's belief rather than a mere majority of members purportedly led past the Holy Spirit. Starting time, since Constantine, the Roman Christian emperor is the temporal shadowy image of the heavenly Christ just as Christ is the eternal blazing sun the earthly emperor reflects, a favorite Neoplatonic principle (Epistle to the Hebrews eight:5, 9:25 & ff., 10:i) . Second, Justinian would have held that the scriptures themselves established his secular authority. No uncertainty, if he knew them (and he must have endorsed the basic ideas if not the actual scriptures) Justinian would have relished New Testament passages where believers were admonished to respect earthly authority as if divine(Epistle to Titus 3:ane; First Epistle to Timothy 2:2;Epistle to the Hebrews 13:17), and to take the premise that God raised and established all earthly rulers, kingdoms, nations and like powers (Isaiah 14:ix). How much more so if the ruler saw himself every bit Christian! Third, still human, a Christian emperor would take some religious oversight of his people merely as a pastor and ecclesiast would accept oversight of his flock. This would afterwards evolve into a fundamental of Authoritarianism in Europe even when the secular power was more discipline to ecclesiastic part. In Justinian's twenty-four hour period, the role of emperor was later all however far more than authoritative than any archbishop or patriarch, partly because the weight of the Roman Empire was all the same at least not so dim a retentiveness and the title of emperor was more or less a thunderous even if vestigial thought. Fourth, Christ himself was seen as a victorious Lord of Hosts over myriad angels, mighty in boxing and apocalyptically wielding a sword in theBook of Revelation (Apocalypse1:16, ii:16, nineteen:xv). Mayhap some would come across the highly visible halo around Justinian equally blasphemous – a Christlike posturing – but he certainly wished credit for trying to unify the Church in E and West, ultimately unsuccessful.

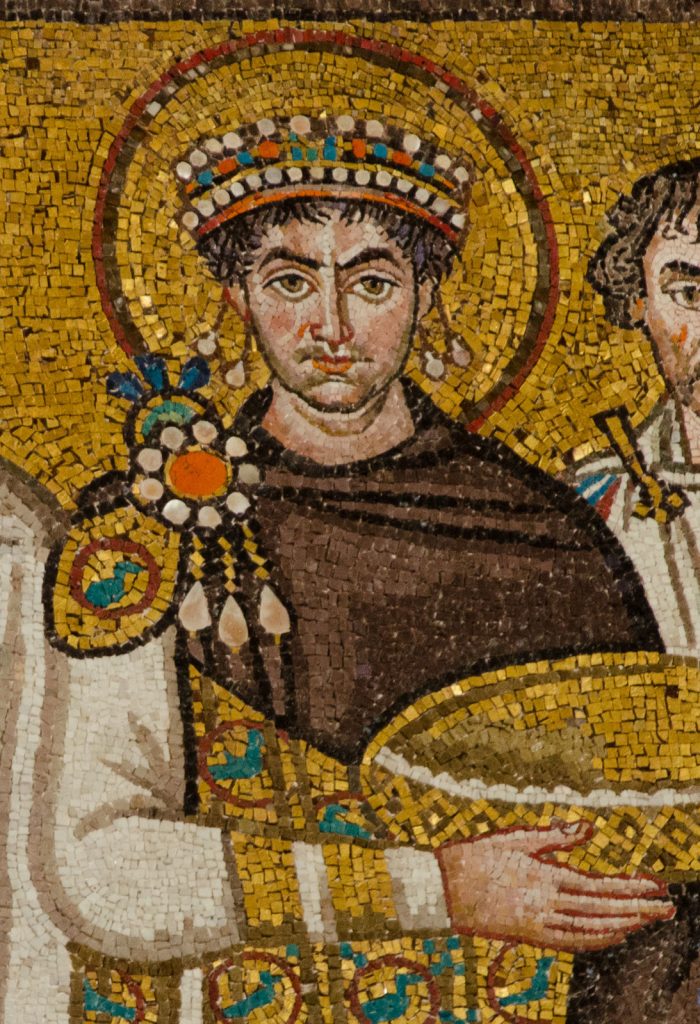

The octagonal Church building of San Vitale was apparently paid for by the broker Julianus Argentarius. The Ravenna mosaic of Justinian, although it is not necessarily a portrait of a 64 year one-time man with graying pilus born in 482 CE whereas the mosaic must be around 546 CE, shows a face used to say-so. A more than likely portrait is at Santa Sophia from 532 CE where Justinian donates the church building to Christ. But it is more than the setting here at Ravenna that is impressive than the homo himself, an apple of silver in a frame of gold, to contrary the Proverb. With Justinian in the center it is like shooting fish in a barrel to come across the symbolism of twelve men flanking him as if he is Christ and they are his twelve disciples. There is notwithstanding some debate if this mosaic duple is meant to represent a procession every bit is often argued, equally if moving into the apse of San Vitale, which I would also maintain. On our correct, mostly clerical power is assembled at his left arm whereas this is counterbalanced by secular political power on our left but at his right. If it is possible to reconstruct some understanding of significance, the leaders of the procession would exist clerical not only because it is a sacred place they are about to enter vicariously but besides because Justinian needs to emphasize from where his earthly ability derives and where it proceeds. But to make it certain his imperial power is very much backed upwardly by armed services strength, the retinue of six soldiers (count six heads) is armed and set up. Over again emphasizing religious continuity, the Chi-Rho shield reminds of Constantine's legendary dream and victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE too as where earthly potency rests on a militant Christ.

Ane of the political statements in this church building may be the reassertion of "Constantinopolitan orthodoxy" against the Arian Goths who controlled Ravenna off and on simply who were expelled for awhile in 540 virtually the fourth dimension the San Vitale decorations including mosaics were planned and soon executed in finished state for the dedication in 548. Thus, "a political message is added to the theological, liturgical and dedicational messages of the sanctuary," (3) whose octagonal grade is best seen from to a higher place.

The officials cannot be easily named, although much has been written about the bright full general Belisarius every bit ane of them, most probable the disguised man on the left wearing the majestic tablinum (?) and with a lozengy insignia on his right shoulder – perhaps a full general's epaulette? – although the old eunuch Narses with the championship ofMagister militum who unremarkably received credit for Belisariius' victories could also be a candidate. Responsible for helping put down the Nika Defection against Justinian in 532, Belisarius was then only twenty-eight, whereas in 546 he would take been fourteen years older at a mature forty-two years. The bearded man standing next to Justinian wears a officeholder'due south or court epaulette [?] on his right shoulder. In and out of favor due to Theodora's jealousy and fright of usurpation, Belisarius had been promoted but toComes stabuli (Count of the Stable) rather thanMagister militumin 544. If the rival general Narses, however, was indeed quondam and certainly a eunuch besides, 1 would expect him to be beardless and mayhap a better good candidate for the official on Justinian'due south left. Nonetheless again some other, probably more likely, suggestion has the official on Justinian'southward left as the patron broker Julianus. I would maintain, equally nearly others have, that a reconciled Belisarius – who as well captured and restored Ravenna to Justinian in 539-xl – is on Justinian's right with the full general's shoulder epaulette insignia [?] and that the patron banker Julianus Argentarius is on Justinian's left and that Narses is non present; the other official is not probable known. Julianus was too plain of Greek origin and possibly acquired part of his wealth through enterprises in overseeing silversmithing. Some evidence exists to suggest he was the banker who donated 26,000 gold solidi for edifice San Vitale. (4) These are difficult identifications to make with any compelling certainty.

At to the lowest degree one of the clerics is easier to identify only considering the archbishop Maximian's proper noun is written over his balding head every bit he carries the crucifix, accompanied by other priests carrying the incense and holding the jeweled Scriptures respectively. Alongside a likely deacon here, Maximian was archbishop of Ravenna from 545-553 so the San Vitale mosaics are possibly his raison d'etre and means of establishing himself alongside Justinian. There are two schools of thought on what Justinian is carrying. The first is that Justinian seems to be carrying the host bread of the Eucharist. The 2nd sugestions is that Justinian carries an empty paten for offering something like the Host (in which ritual technically merely a priest should minister). It makes some sense for this to be connected to the Eucharistic ritual for symmetry if Theodora carries the sacramental wine or at least the chalice. associating Justinian even more with Christ every bit the redemptive Bread of Life (or sacrificiant High Priest). Justinian also serves only as easily here as the imperial provider and Redeemer of his people, especially considering his frustrated mediatorial role betwixt East and Westward. Although neither Justinian or Theodora were ever present in Ravenna is immaterial; their imperial presence is maintained through these statements of authority for eternity rather than for a cursory dedicatory moment. The builders and planners thereby also obtain vicarious dominance and orthodoxy by invoking the glory of the emperor and empress.

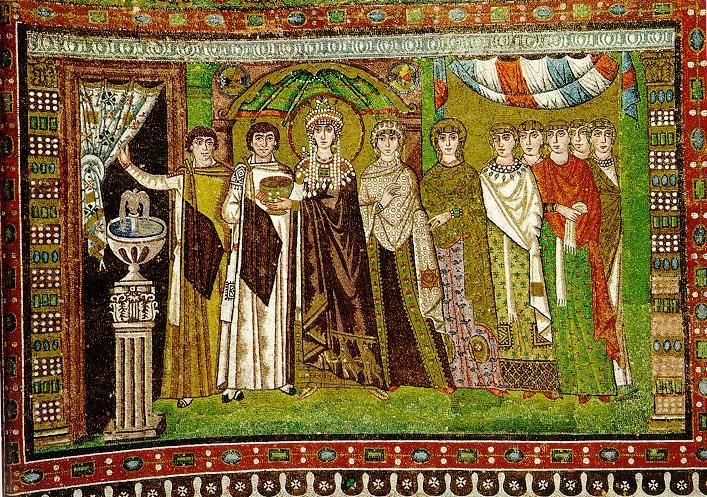

On the opposite mosaic, Theodora'southward prototype is mayhap more a portrait, probably giving a glimpse of her ruthless ambition. Drenched in pearls and nether a shell alcove evoking Venus whom she bodily served more theTheotokos, Female parent of God, yet she is likewise haloed and the center of focus as peradventure some like Procopius idea only a Mary ought to be every bit Blessed among Women. Her retinue besides consists of several officials processing in forepart – one an unidentified full general? – as she carries the chalice of Holy Wine (or at to the lowest degree the empty chalice) likely to represent Christ's sacrificial claret. Merely this is again problematic considering only a priest should be so consecrated to minister herein. Her officials even open the pall, perhaps symbolic of the Temple Veil, for her imminent entry into a Holy of Holies. That these propagandizing ideas of Theodora'south sanctified purity – perhaps an ironic compensation for her notorious background – were a travesty for Procopius, who raked her more severely in his writing than any other person, seems less remarkable through history now than up close at the time, yet transformational a conversion she might have had. This is somehow despite her swift executions eliminating rivals and her strident position of Empress with a throne alongside Justinian leading her biographers to have often suggested that she was the real power behind the Majestic Christian ruler Justinian claimed to be, greatly influencing her husband beyond the norm.(five) Theodora, co-ordinate to Procopius, was a old young whore who took on all comers by the dozen when she had worked as a circus performer. Eventually she rose to the slightly less onerous role of courtesan – although the boldest and most infamous in Constantinople – and eventual mistress to an ambassador before possibly setting her sights on Justinian whom she married in 525, having herself crowned empress in 527 with Justinian equally emperor. Theodora was unstoppable in the 6th century; nosotros can only imagine her in the Twentieth or Xx-first!

Here is part of Procopius' annihilation but hagiography of Theodora:

"Never was a woman so completely abandoned to pleasure. Many times Theodora [before her "gentrification"] would banquet with x young men who had a passion for fornication…afterward exhausting them she would go to their attendants (by now more than 30) and copulate with them too in an futile effort to satisfy her

unquenchable lust…Although she made ample utilise of the three apertures Nature

gave her body, she complained her nipples needed openings to attempt intercourse

at that place as well…In the theater she would lie naked and spread herself out, having

trained hungry geese to selection off grain sprinkled by slaves over her individual parts…" (vi)

Now nosotros probably see Procopius' demonizing and little business relationship every bit most unfair and possibly inspired or at least influenced by prior accounts of Messalina in Rome. That geese were a symbol of Aphrodite, the divine patroness of courtesans, was not lost on Procopius. Only in a patriarchal world, Theodora was first a savvy entertainer and then a political power in her ain correct. She was unflinching as empress and the backbone for Justinian in the Nika revolt when he would have fled and she refused to budge. Facing the threat of decease, which she would prefer to abdication or flying, Theodora said "Imperial purple makes a very fine shroud." (7) As Bustacchini and others have long pointed out, Theodora'due south wearing apparel also shows a procession of the Persian Magi with Phrygian caps bringing gifts as she does – very like to that nearby mosaic scene at Sant' Apollinare Nuovo – equating her with wisdom (sophia) and perhaps a further propagandizing effort to forge an identity with the Hagia Sophia itself as her shell alcove behind her testifies to her near-divine importance.

I of Theodora's retainers pictured here below, mayhap closest to her firsthand left, was likely to take been the far more royal Princess Julia Anicia, herself daughter of a previous emperor, Anicius Olybrius (before Justin) and ultimately descended from Constantine, the patroness of greater basilicas in Constantinople than anything other than Santa Sophia and possible its equal, although Justinian likewise built 25 churches in Constantinople alone. These three ladies immediately behind Theodora (on her left, our right) are the virtually eminent, 1 of them (middle) possibly Antonina, the married woman of Belisarius (perhaps shown by the insignia on her dress hem that matches his general's shoulder epaulette [?]) and also a close friend of Theodora. One other possibility is that it is Joannina, daughter of Belisarius and Antonina, who was married to the regal grandson Anastasius. The mosaicist's mastery of shading shows best on the priceless white silk garments of the purple lady on the far left closest to Theodora.

When Justinian stood inside the newly finished Santa Sophia in 537, it may have been symbolically to Theodora his famous anecdotal whisper: "Solomon, I have surpassed you." Justinian is discredited with losing as much of Byzantium as gaining and was infamous even in his day for his extravagances equally an importer of luxury goods, monumental builder and art patron. Mayhap information technology was Theodora who persuaded him how immensely valuable silk was for him to eventually send a few monks to Cathay to steal silkworms in hopes of starting a rich Byzantine silk manufacture and thereby become independent of Persia's wealthy middlemen monopoly, which he did on a grand scale once the bamboo with purloined silkworms arrived intact having survived the long and arduous journey from China. (viii)

Power in politics and religion is mayhap rarely better expressed, as Bustacchini, Pegues and many others too annotation, establishing the intended connectedness in both subtle nuance and clear symbol.(9) That these Ravenna mosaics likewise help set up an artistic precedent for subsequent Byzantine monumental portrayal in mosaic, while following tradition, is also maintained strongly here, a formal symmetry that Rice calls "rhythmical composition". That these mosaics are fascinating gauges of ability in the early Byzantine world is a given. Perhaps they are best mensurate of Byzantine imperial appetite likewise. "[N]o other work of art . . . conveys the spirit of Byzantium with then much eloquence equally do these two mosaics." (ten) The flatness of frontal pose, dominant for a static millennium in Byzantine art, makes it difficult to gauge movement or anything across monumental eternity. Yet, according to Rice, "No greater or more enlightened patron of art than Justinian has ever lived". (xi) The best authority on early Byzantine military matters would exist Treadgold, who also addresses the San Vitale contexts in careful scholarship. (12) As Cameron notes on how complicated it is to understand Justinian, "Contemporary sources accept left us a deeply contradictory fix of impressions of the emperor." (13) Extravagant and self-serving patron with grandiose religio-political and military ambitions may likewise exist added to Justinian'southward complex incentives for his rule and his propagandizing motives, although he oft seems overshadowed by Theodora, making him appear weaker than he could otherwise be perceived. If Christ never intended to dominion over the Romans in this earth, Justinian (and most likely Theodora) certainly did.

Notes

- David Talbot Rice.Art of the Byzantine Era. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997 repr., 9.

- John Julius Norwich.Byzantium: The Early Centuries. London: 1988;A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Knopf, 1997, 82.

- Lyn Rodley.Byzantine Art and Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 84-5

- Gianfranco Bustacchini.Ravenna: Capital of Mosaic. Ravenna: Cartolibreria Salbaroli, 1988, 26.

- Owen Chadwick.A History of Christianity. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995, 169.

- Procopius.Works. seven vols. H. Dewing, tr./ed, London, 1940.

- Peter and Linda Murray.Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, 284, quoting Procopius and others.

- Patrick Hunt. "563 CE: How the Byzantines Caused Silk."Bang-up Events in History: The Aboriginal World vol. 1, Salem Printing, 2004,

- Emily Pegues, "The Mosaics of St Vitale, Ravenna", Sweet Briar Higher Art History Senior Seminar, 2000, http://www2.students.sbc.edu/pegues00/seniorseminar/vitalemosaics.html.

- Otto von Simson.Sacred Fortress: Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1948, 27. Also quoted in Pegues and elsewhere.

- Rice, 47

- Warren Treadgold. "Procopius and the Regal Panels of San Vitale,"Art Bulletin79 (1997): 708-23. (Co-author). Also see hisByzantium and Its Army. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

- Averil Cameron. "An accompaniment to Justinian and his age."Journal of Roman Archaeology 19 (2006) 721. This argument is found in her review of M. Maas, ed.The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, 2005.

Published by Stanford University, 07.12.2006, nether the terms of an open access license.

Comments

Source: https://brewminate.com/byzantine-art-as-propaganda-justinian-and-theodora-at-ravenna/

0 Response to "Why Do Some Historians Believe Byzantine Art Included Government Propaganda"

Post a Comment